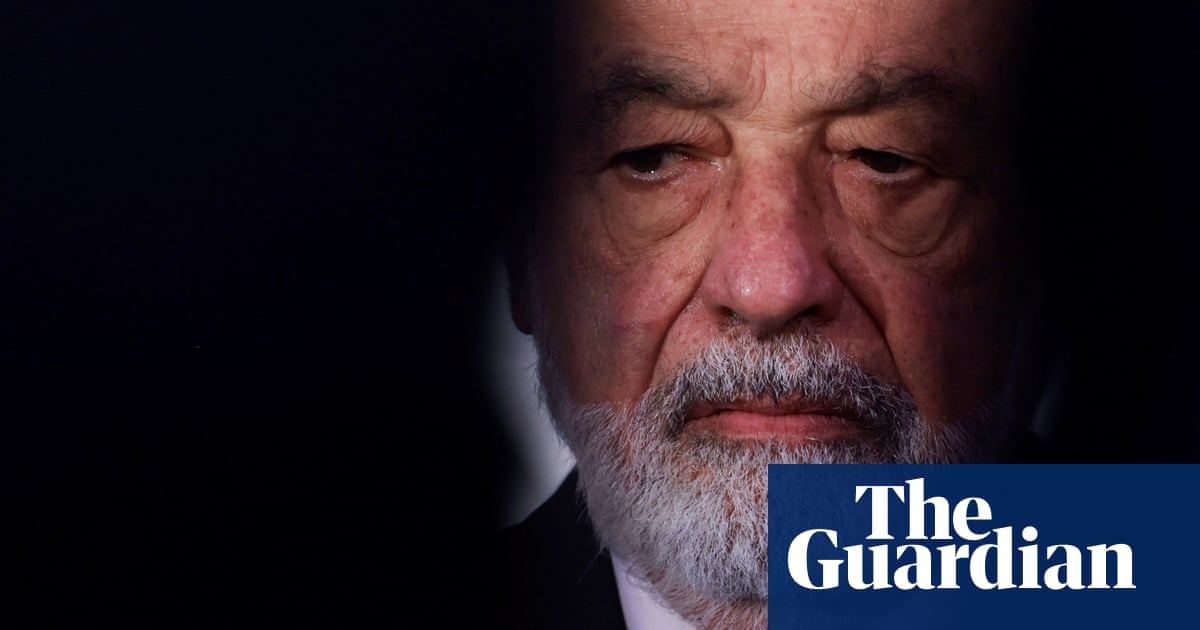

Carlos Slim, the Mexican billionaire who this week paid £400m for a 3% stake in BT, has traversed some of life’s highest peaks and lowest ebbs.

He claims that in 1997, aged 57, he was briefly declared dead after suffering a massive haemorrhage on the operating table at the Texas Heart Institute during surgery to replace a faulty heart valve.

Thirteen years later he was named the world’s wealthiest man by the American business magazine Forbes, his fortune estimated at $73bn.

While Slim, the son of Lebanese immigrants, has fallen off the list of the top 10 richest people in the world amid the rise of tech bros such as Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg, his net worth has swollen to $93bn.

What’s more, his investment in BT shows that at the age of 84 he has not lost his renowned appetite for opportunistic investment, swooping on the company’s shares at a time when many analysts are predicting a brighter future under the new chief executive Allison Kirkby.

Investors appeared cheered by Slim’s latest move: BT’s shares rose 4% on Thursday. He’s not the only billionaire on the share register: Altice, the group controlled by Moroccan-born telecoms mogul Patrick Drahi, is its largest shareholder.

BT and Slim seem a good fit. The Slim empire was founded on telecoms, in particular América Móvil, which secured a virtual monopoly on the telephone business in Mexico, a country of more than 100 million people.

But Slim also has interests in a sprawling array of sectors, including manufacturing, retail, energy and aviation.

Many of his investments are housed within Grupo Carso, a holding company whose title is a portmanteau of the first letters of his own name and that of his late wife, Soumaya Domit, with whom he had six children.

Slim cuts a divisive figure in Mexico, according to his biographer, Diego Enrique Osorno, author of Slim: A Political Biography of the Richest Mexican in the World. “There are Mexicans who look at Slim with pride and see him as an aspirational figure … and there are those who consider him to be the symbol of our inequality,” said Osorno.

Slim is known for taking a simple but effective approach to investing, swooping on undervalued assets in times of economic turmoil and picking up bargains amid market panic.

Amid the global financial crisis that began in 2008 he snapped up a $150m stake in the Wall Street bank Citigroup and loaned $250m to the New York Times – saving it from bankruptcy, by some accounts.

He is said to have picked up his shrewdness for a deal from his father, Julián Slim Haddad, who arrived in Mexico in 1902 in order to avoid conscription into the Ottoman army. The Lebanese immigrant is said to have given his children ledgers to help them understand how to interpret financial transactions.

skip past newsletter promotion

Sign up to Business Today

Get set for the working day – we’ll point you to all the business news and analysis you need every morning

Privacy Notice: Newsletters may contain info about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. For more information see our Privacy Policy. We use Google reCaptcha to protect our website and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

after newsletter promotion

The young Slim, who was a keen baseball player in Mexico City’s middle class Polanco suburb, would trade baseball cards in the playground, keeping a weather eye on his accounts. By 11 he had already bought his first government savings bonds. By 15 he had invested in Banco Nacional de México. Upon leaving university, he became part of a clique known as “los Casabolseros” – a group of slick young stock market players.

According to Osorno and the political commentator Denise Dresser, the mathematical nous Slim gleaned during his childhood, together with his vision for a deal, have played a part in his success, but so too has an instinct to stay on the right side of political elites at opportune moments. Many of his business interests were picked up at rock-bottom prices during privatisations by a cash-strapped state.

“Slim emerged as a Mexican prototype of the Russian oligarchs, as someone who multiplied their fortunes under the shadow of power,” said Dresser.

Unlike some Russian oligarchs, though, Slim developed a reputation for maintaining a low profile, eschewing flamboyance or showy megamansions, with the possible exception of the Duke Semans mansion, an eight-storey home on New York’s Fifth Avenue which he bought for $44m in 2010.

Slim does spend some of his vast fortune on art, though; his home has sculptures by Rodin, and paintings by Renoir and Van Gogh. In 1999, his wife died. Slim built an art museum and named it in her honour.