If you strain your memory very hard, you might recall a man named Robert Mueller.

Only a short year ago, the special counsel was the man of the hour. Now, in the middle of a pandemic, a protest movement over police violence, and a presidential campaign, the urgency of Mueller’s findings has—understandably—faded. Nevertheless, both Congress and news organizations are still pushing to squeeze more information out of the Mueller report. The Supreme Court will hear a dispute over whether the House of Representatives may access grand jury material redacted from the report, while litigation by various news organizations has resulted in the release of search warrants and affidavits related to the Roger Stone investigation and tranche after tranche of summaries of FBI interviews conducted by Mueller’s team.

And most recently, BuzzFeed News and the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) successfully sued for the release of a version of the Mueller report with many fewer redactions—uncovering new text written by Mueller’s office that has been hidden for the past year.

So what fresh material is available in the new, improved, less-redacted Mueller report?

In one sense, not very much. The redactions lifted by BuzzFeed and EPIC’s litigation all pertain to the case of Roger Stone, which was pending when the report was first released but has now been completed—hence the court’s willingness to release this material. As a result, a fair amount of the newly unsealed material had already become public when the government presented it during Stone’s trial. Other pieces of the material were previously reported on by news organizations or, in one case, presented to Congress and the public by the witness who told Mueller about the incident in the first place.

But there are a few shreds of information that are really, genuinely new, and they’re damning of the president. Namely: Trump had direct knowledge of Roger Stone’s outreach to WikiLeaks, according to multiple witnesses interviewed by Mueller. He encouraged that outreach and asked his campaign chairman to pursue it further, those witnesses said. And Mueller’s office appears to have strongly suspected, without putting it in so many words, that Trump lied to the special counsel in his written answers to Mueller’s questions about the Stone affair.

The redacted report hinted at this. But it’s another thing to see it spelled out unmistakably by the special counsel.

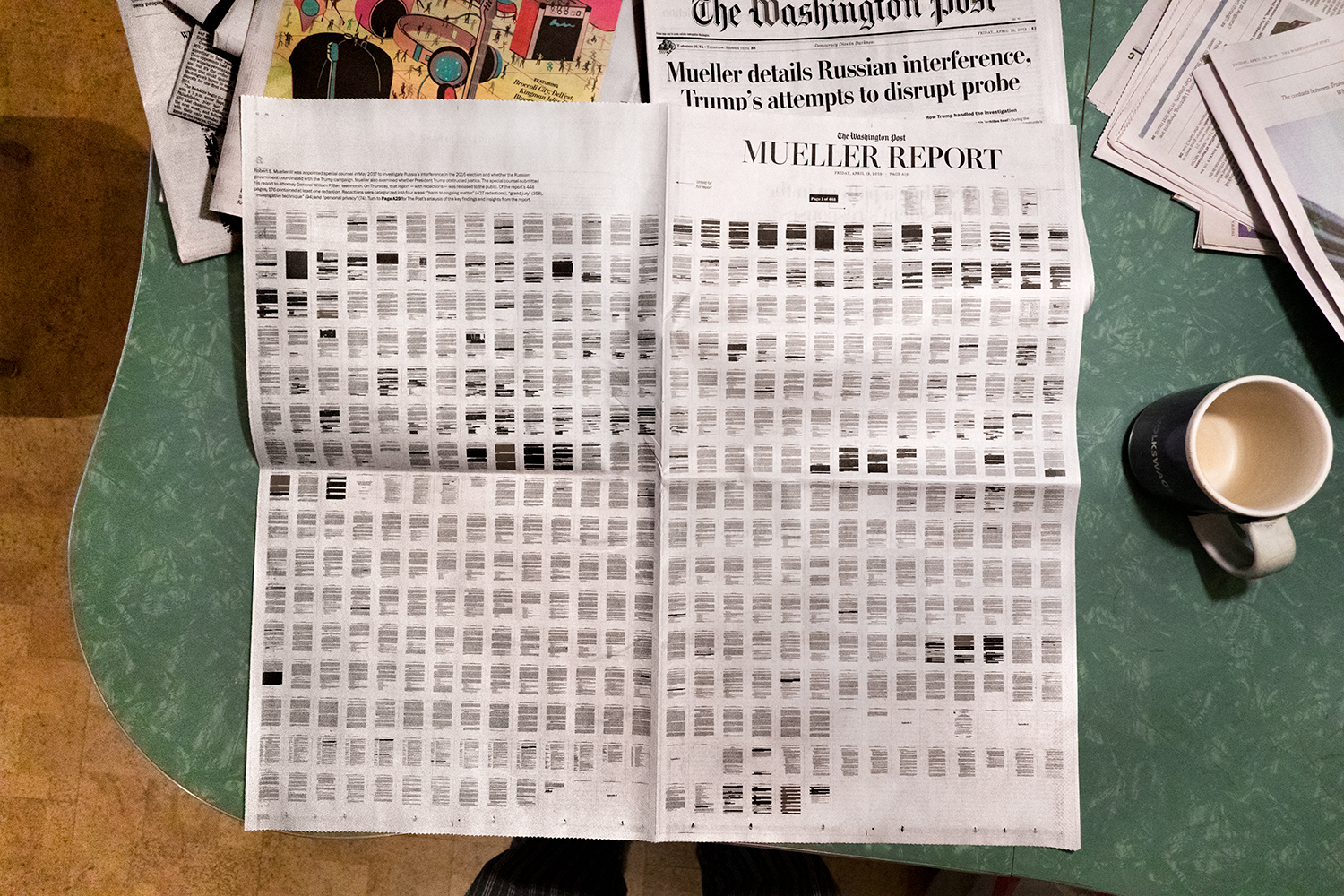

Given that the full text of the original report is a hefty 448 pages, and the BuzzFeed/EPIC version clocks in at 394, it’s not that easy to find the fresh material at a glance. Below, I’ve set out the redacted pages from the original report alongside their newly unredacted copies. You can scroll through the PDF documents (available directly here and here) and see what changed from copy to copy. If you click through to the PDFs themselves, the unredacted text is highlighted in yellow.

To keep things streamlined, I’ve included only the pages where redactions were lifted. If you want to read the full report as it appears in the BuzzFeed/EPIC release, including the pages where nothing changed from the original, you can do so here. The report as first released to the public in April 2019, including all redactions, is available here.

You’ll also find below a breakdown of what unsealed information is available, listed by page number and separated by volume. In each case, I’ve put together short descriptions of the newly available facts, incorporating quotes from the relevant sections of the Mueller report along with my own summary text. I’ve attempted to note instances where information was previously available and flagged where readers might find those earlier accounts. If a fact is stated on multiple pages, I’ve included it only once.

Volume I

“…Roger Stone made several attempts to contact WikiLeaks founder Assange, boasted of his access to Assange, and was in regular contact with Campaign officials about the releases that Assange made and was believed to be planning.” (Vol. I, p. 51)

This is the overarching theme of the newly unsealed information—much of which became public in the indictment of Stone in January 2019 and over the course of Stone’s trial. It’s the details that follow that are more noteworthy.

“…beginning in June 2016 and continuing through October 2016, Stone spoke about WikiLeaks with senior Campaign officials, including candidate Trump.” (Vol. I, p. 51)

While the redacted report hints at involvement by Trump, the hidden material makes this frustratingly unclear. The unredacted copy directly states that Trump spoke multiple times with Stone about WikiLeaks’s release of material damaging to Clinton. Specifically, according to the report, Stone told the Trump campaign “as early as June 2016”—that is, at least a month before WikiLeaks began its releases on July 22—that Assange would release damaging documents.

Much of this material became public during Stone’s trial thanks to Rick Gates, a campaign official indicted as part of the Mueller probe who testified against Stone. Gates testified then that he and campaign chairman Paul Manafort spoke with Stone about future WikiLeaks releases in June, and that the campaign’s interest in what Stone had to offer peaked after July 22—that is, after it turned out that Stone’s information might have been accurate. According to Gates, Manafort expressed interest in more information on WikiLeaks and asked Gates to keep in touch with Stone about possible future releases.

All this is now also documented in the unredacted report—much of it, footnotes show, derived from FBI interviews with Gates. But the report also documents matching testimony from Manafort himself, who told Mueller’s office that “Stone told Manafort he was dealing with someone who was in contact with WikiLeaks and believed that there would be an imminent release of emails by WikiLeaks” (Vol. I, p. 52).

According to Michael Cohen, Stone told Trump in a phone call before July 22 that “he had just gotten off the phone with Julian Assange and in a couple of days WikiLeaks would release information.” After the July release, Trump “said to Cohen something to the effect of, ‘I guess Roger was right.’” (Vol. I, p. 53)

Cohen informed Congress of this incident in his public testimony in February 2019—which is cited in the report itself, along with an FBI interview of Cohen. During his testimony, as the report notes, he estimated that the Stone call took place on July 18 or 19. In Cohen’s account, he was in Trump’s office in Trump Tower when Stone called and Trump put the call on speakerphone, allowing Cohen to hear.

The fact that Trump later commented “I guess Roger was right” (according to Cohen) is new, however.

After the first WikiLeaks dump, Manafort spoke with Trump about Stone’s apparent foreknowledge of the release. Trump “responded that Manafort should stay in touch with Stone. Manafort relayed the message to Stone[.]” (Vol. I, p. 53)

Gates’s testimony in Stone’s trial gave part of this story: Gates told the jury that Manafort asked him to keep in touch with Stone about upcoming WikiLeaks releases and that Manafort said he personally would keep others on the campaign updated, “including the candidate.”

Now, though, the unsealed portions of the report give Manafort’s side of the story as well, revealing that Manafort spoke directly with Trump and that the directive for campaign officials to keep up with Stone came from Trump himself. (The footnotes to portions of the text describing claims by Manafort are still redacted, and are labeled in the original report as redacted grand jury material—consistent with court documents that show Manafort testified twice before the grand jury.)

“Gates also stated that Stone called candidate Trump multiple times during the campaign. Gates recalled one lengthy telephone conversation between Stone and candidate Trump that took place while Trump and Gates were driving to LaGuardia Airport. Although Gates could not hear what Stone was saying on the telephone, shortly after the call candidate Trump told Gates that more releases of damaging information would be coming.” (Vol. I, p. 54)

The original report included a tantalizing redaction—the only text available of the material quoted above described a car ride with Trump and Gates to the airport, and the fact that Trump told Gates to expect more “damaging information.” Now it’s clear that Trump got that information from Stone himself. But this material was revealed in the Stone trial, too—Gates’s testimony made headlines at the time.

“Stone also had conversations about WikiLeaks with Steve Bannon, both before and after Bannon took over as chairman of the Trump campaign” in August 2016—telling Bannon after he became chairman that WikiLeaks would soon release material damaging to the Clinton campaign. (Vol. I, p. 54)

This, too, became public during the Stone trial—in this case thanks to testimony by Bannon himself.

Page 47 of the unredacted report also includes more information about the back-and-forth between Bannon and Stone, some of which was previously available in the Stone indictment and all of which was subsequently published in the form of email exchanges released by the New York Times. On Oct. 3, 2016, Breitbart editor Matthew Boyle—named in the report only as “a reporter”—emailed Stone to ask about Assange’s plans. Stone responded, “I’d tell Bannon but he doesn’t call me back.” The next day, after a confusing press conference by Assange, Bannon wrote to Stone asking, “What was that this morning???” and whether Stone had “cut deal w/ clintons???” Stone responded that Assange was afraid he would be killed and that “a load [of information would be released] every week going forward.”

Following the initial July 22 release, Stone reached out to right-wing media personality Jerome Corsi instructing him to “[g]et to Assange … and get the pending [WikiLeaks] emails[.]” Corsi began his own outreach to Assange through an associate, Theodore Malloch. On Aug. 2, Corsi wrote to Stone, “Word is friend in embassy plans 2 more dumps. One shortly after I’m back. 2nd in October. Impact planned to be very damaging.” (Vol. I, p. 52)

Shortly after this exchange, Stone made “the first of several public statements” announcing he had been in touch with Assange, the report states, though he later said that “the communication was via ‘a mutual friend’”—presumably Corsi.

This information was previously available through the Stone indictment and the draft statement of offense in Corsi’s case. (Corsi entered plea negotiations with Mueller’s team, he says, but later called off the negotiations and provided the draft statement to the Washington Post. No charges have been brought against him.)

Stone also reached out to Assange through New York radio host Randy Credico, beginning in August 2016. At one point Stone asked Credico to ask Assange for certain emails from Clinton or the State Department, which Credico did. Then, “[i]n late September and early October 2016, Credico and Stone communicated about possible WikiLeaks releases.” (Vol. I, pp. 56-57)

This back-and-forth between Credico and Stone is documented in the Stone indictment, though Credico is not named. The radio host shared his account of his interactions with Stone as a witness in Stone’s trial.

Stone emailed prominent campaign donor Erik Prince about Assange on Oct. 3 and wrote that “the payload is still coming.” Stone told Prince by phone that “WikiLeaks would release more materials that would be damaging to the Clinton campaign” and “indicated to Prince that he had what Prince described as almost ‘insider stock trading’ type information about Assange.” (Vol. I, p. 57)

The Stone indictment includes information about Stone’s “payload” email and the phone call, though Prince is described only as “a supporter involved with the Trump Campaign.” Prosecutors revealed that the mysterious supporter was Prince during Stone’s trial.

Mueller investigated whether Stone was involved in WikiLeaks’s Oct. 7 release of emails belonging to Clinton aide John Podesta—a release that took place only hours after the Washington Post published the Access Hollywood tape. But the special counsel found little evidence. (Vol. I, pp. 58-59)

The original text of the redacted report described conflicting evidence as to whether Corsi had reached out to Assange to encourage WikiLeaks to release the emails following the Access Hollywood story. (To some extent, that conflict seems to have stemmed from Corsi’s own unreliability: By Mueller’s account, Corsi contradicted himself multiple times over the course of his interviews with the special counsel.)

Now, the unredacted text shows that Stone was also a part of this drama. According to Corsi, Stone reached out to him before the Post published the story and seemed to know about the tape. Corsi told the special counsel’s office both that he told Stone to reach out to Assange and suggest WikiLeaks publish further emails, and that Stone told Corsi to do so. Corsi himself made some of this information public in his book about his experience of the Mueller investigation, published January 2019—as Andrew Prokop exhaustively describes at Vox—but given Corsi’s slipperiness with the truth, it’s useful to have Mueller’s account of the matter.

If Stone and Corsi really had connected with Assange on Oct. 7, it could be significant: it would mean that figures connected with the Trump campaign pushed for a WikiLeaks release to distract attention from the Access Hollywood tape. But as Mueller wrote in the original, redacted report, his office “found little corroboration” for Corsi’s various accounts of the day. Phone records show a call between Stone and the Post on Oct. 7, and calls between Corsi and Stone, but that’s it.

Stone lied to the House Intelligence Committee in May 2017, denying any efforts to reach out to Assange. He also threatened Credico to prevent Credico from testifying and contradicting Stone’s statements to the committee. These actions were the basis of the criminal charges against him. (Vol. I, pp. 196-197)

This material is available in the Stone indictment.

Volume II

When then-Senate Intelligence Committee Chairman Richard Burr briefed the White House about the Russia investigation in March 2017, he appears to have provided information about Stone’s case as well. Notes from Deputy White House Counsel Annie Donaldson include the line “Stone (can’t handicap).” (Vol. II, p. 52)

The redacted report made clear that Donaldson’s notes discussed former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn, Manafort, former campaign foreign policy adviser Carter Page and former foreign policy adviser George Papadopoulos (“Greek Guy”). The portion of the notes discussing Stone was previously redacted. It’s not clear what Donaldson might have meant by “can’t handicap.”

Mueller’s analysis of Trump’s efforts to obstruct the investigation by dissuading witnesses from testifying included Trump’s tweets about Stone, as well as his actions toward Paul Manafort and Michael Flynn. (Vol. II, pp. 128-133)

Among the instances of potential obstruction of justice analyzed in Volume II of the report, Mueller includes Trump’s conduct toward Flynn, Manafort, and what until now was a redacted third individual (along with Michael Cohen). Context made fairly obvious that Stone was the third person. (An enterprising reader could, for example, Google the various quotes and news headlines included in this section from which the third person’s name had been redacted, and see that these snippets referred to Stone.) But now it’s spelled out in black and white.

Much of this newly unredacted Stone section is more or less what one would expect. As with the sections on Manafort and Cohen, it describes the president’s public tweets and other statements discouraging cooperation with the government. At one point, for example, Mueller notes Trump’s December 2018 tweet that Stone had “guts” in declining to “make up lies and stories about ‘President Trump.’” (In fact, Susan Hennessey and I analyzed this tweet as possible obstruction of justice at the time.)

The Manafort and Flynn sections of the report both included public statements by the president along with evidence of previously unknown, behind-the-scenes maneuvering by Trump and his team to keep witnesses from testifying. The new Stone section, on the other hand, includes only Trump’s public tweets: There’s no hidden strong-arming here.

Mueller does, however, strongly imply in the unredacted text that Trump lied to the special counsel’s office—perhaps the biggest bombshell to come out of this new material.

The special counsel acknowledged during his congressional testimony that Trump had been less than entirely truthful in his written answers to questions posed by Mueller’s team. Until now, though, few specifics were available about the nature of those untruths. Readers were left to sift through Trump’s answers—appended to the report itself—and draw their own conclusions. The unredacted report, though, shows that Mueller’s office doubted the honesty of Trump’s assertions that he did not remember any discussions about WikiLeaks with Stone. The relevant paragraph is worth reading in full:

With regard to the President’s conduct towards Stone, there is evidence that the President intended to reinforce Stone’s public statements that he would not cooperate with the government when the President likely understood that Stone could potentially provide evidence that would be adverse to the President. By late November 2018, the President had provided written answers to the Special Counsel’s Office in which the President said he did not recall “the specifics of any call [he] had” with Stone during the campaign period and did not recall discussing WikiLeaks with Stone. Witnesses have stated, however, that candidate Trump discussed WikiLeaks with Stone, that Trump knew that Manafort and Gates had asked Stone to find out what other damaging information about Clinton WikiLeaks possessed, and that Stone’s claimed connection to WikiLeaks was common knowledge within the Campaign. It is possible that, by the time the President submitted his written answers two years after the relevant events had occurred, he no longer had clear recollections of his discussions with Stone or his knowledge of Stone’s asserted communications with WikiLeaks. But the President’s conduct could also be viewed as reflecting his awareness that Stone could provide evidence that would run counter to the President’s denials and would link the President to Stone’s efforts to reach out to WikiLeaks. On November 28, 2018, eight days after the President submitted his written answers to the Special Counsel, the President criticized “flipping” and said that Stone was “very brave” for not cooperating with prosecutors. Five days later, on December 3, 2018, the President applauded Stone for having the “guts” not to testify against him. These statements, as well as those complimenting Stone and Manafort while disparaging Michael Cohen once Cohen chose to cooperate, support the inference that the President intended to communicate a message that witnesses could be rewarded for refusing to provide testimony adverse to the President and disparaged if they chose to cooperate.

In other words, Mueller suspected that Trump may have lied in his answers to the special counsel’s office. Then, he suspected, the president may have pushed Stone not to testify in order to prevent Mueller from discovering that deception.